It has been a while since my last post but it’s time to get back to posting more frequently.

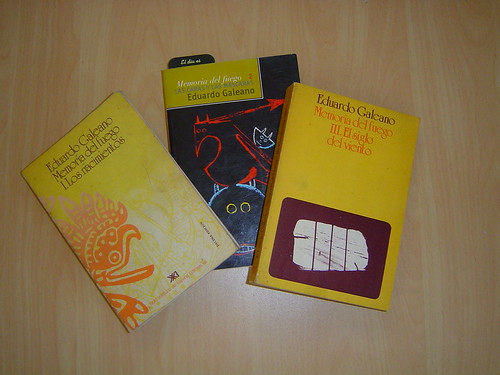

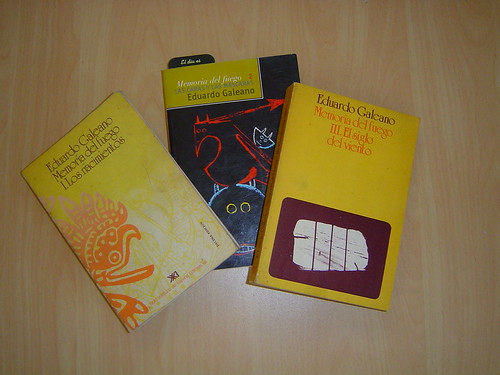

A few posts back I talked about a series of remarkable books by the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano: Memoria del Fuego

I already had a copy of the second volume of this work in English but I wanted to get all three volumes in Spanish. I had assumed, initially, that finding these three books by Galeano would be rather simple in Buenos Aires. After all, Buenos Aires has a lot of bookstores, people read a lot in this city, the books are definitely not obscure and Galeano is a well-known writer in this area.

Indeed, just before starting my search I did happen to see volume 3, El Siglo del Viento, at the Musimundo on Florida. But I figured then that I could easily find it elsewhere and didn’t want to give my book money to a place like Musimundo.

A few days later I went off to El Ateneo on Av Santa Fe. It’s such a gorgeous bookstore but, honestly, I seldom find the books I’m looking for in El Ateneo especially when it comes to literature.

Of course, one of the difficulties with locating Memoria del Fuego (or most books by Galeano) is defining the genre. Is it history? Is it literature? Or a little of both? Generally, all the Galeano books (and he’s quite prolific) are shelved together but the easiest is to ask the store clerk.

Then I wandered over to Av Corrientes. I’m very familiar with the selections in the used bookstores on Corrientes and knew that I’ve not seen Memoria del Fuego before but I tried again. I also tried Libreria Hernandez, which I often feel has a very good literature selection.

(As a side note, I do think that Libreria Hernandez definitely has the best English literature in Spanish translation). But no Memoria del Fuego at Hernandez.

Then I thought Gandhi, that’s a really good bookstore. They’re sure to have….but nope. The sales clerk at Gandhi was quite helpful and suggested trying Parque Rivadavia….more on that later, but I wasn’t yet ready to give up the search in a regular bookstore. Heck, I even checked the Musimundo on Corrientes but they didn’t have it and neither did Zival’s.

I was getting concerned by this time and was wondering what was up with this book. After all, the Washington Post called this book “an epic work of literary creation”. So, why is it so difficult to find in Buenos Aires, the city that prides itself on its bookstores?

I headed down Callao to check out the little bookstore at the back of Clásica y Moderna. They have a quality selection. But the woman there said that they didn’t work with that publisher. Hmmmm.

Then there’s another small bookstore on Callao just down from Clásica y Moderna. They didn’t have it either. But the clerk said that he believed the book was going to be reprinted later this year. Fine and good, if true, but I wanted the books now and not months later.

So, I finally decided to head back to Musimundo on calle Florida and buy the volume 3 that I had seen there earlier. But, of course, once I finally make it back to the store I find that the book is no longer there.

Okay, the hunt wasn’t over. I went down the street to try the El Ateneo on Florida. The clerk looked baffled and said that they hadn’t had those books in a long time. But he said that they did have El fútbol a sol y sombra by Galeano. No! I didn’t want just any book by Galeano and I certainly didn’t want one on soccer!

Then I went across the street to the Cúspide. They didn’t have the book but their in-store computer reported that the books were available at both the Cúspide branches on Santa Fe and in Village Recoleta. Yeah!!!

So, I hiked up Av Santa Fe from Florida to the Cúspide store just past Callao. I think that whoever manages that store is a frustrated librarian. The store is organized by very specific subject matter. Anyway, they didn’t have the book either. Sigh. Okay, so I went over to Village Recoleta, again where the computer states all the volumes are in stock.

Like most Cúspide stores the Village Recoleta branch is arranged in a matter so that it’s almost impossible to find a specific book without asking for it. And why was I not surprised when the clerk said that they didn’t have the book in stock? But what about the computerized inventory stating that the books are in that store? The clerk says that the inventory is wrong.

Memo to Cúspide: Spend some money and fix your computerized database! Otherwise, what’s the point of having it?

Oh, amusingly, the young guy working at Cúspide quickly pulls a slim green volume from the Galeano shelf and says that they do have El fútbol a sol y sombra.

Memo to guys working in bookstores: I know this will sound weird but not every guy in the world is a fútbol fan.

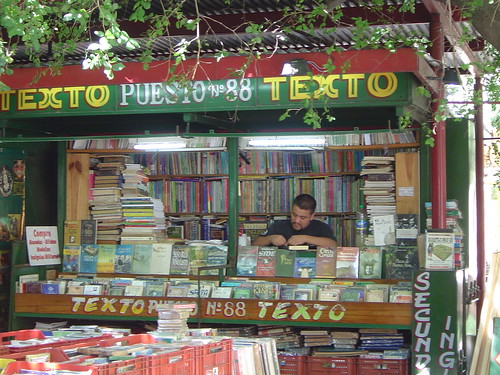

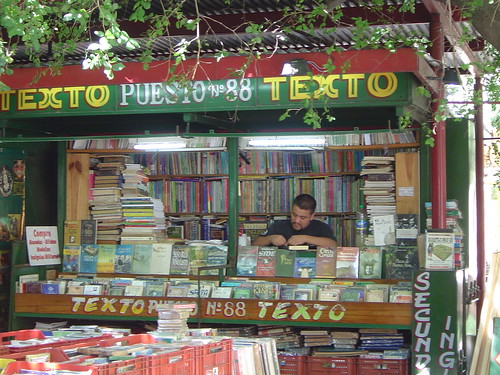

Parque Rivadavia

So, trying to find Memoria del Fuego turned out to be a long, frustrating process and it was finally time to try the used book stalls in Parque Rivadavia. At least, it was a good excuse to take the A line on the subte.

The booksellers at Parque Rivadavia are similar to the used bookstores on Av Corrientes. For the most part, both have about the same selection. At Parque Rivadavia you have to go around to each book stall. Each seller has a very good idea of his offerings so it’s easiest just to ask.

I felt really lucky when halfway through the stands we found one seller with the first two volumes. Hurray!

But what about the third? Found it at the very last book stall in Parque Rivadavia. Success!!

Of course, none of these sellers seemed to have multiple copies so if you go searching now for Memoria del Fuego in Buenos Aires then you probably will just be out of luck until the books are reprinted.

Memory of Fire

Oddly, the last time I was in Walrus Books, the best English language bookstore in Buenos Aires, I did see all 3 volumes of Memory of Fire by Galeano in its English translation. So, in this case, it’s easier to find the English translation of a book by a noted South American writer than it is to find the original Spanish. Something is wrong about that.

Of course, it’s likely the publisher’s fault for not printing enough copies rather than the fault of the booksellers. But the booksellers could be a lot more helpful. I recall being surprised by the staff at Border’s in Aventura, Florida when I inquired about a book that was not in the store. Rather than offering to order the book for me, the person at Border’s immediately got on the phone and called the Barnes & Noble down the street, which had the book. I went to B&N and brought the book that day but became a regular visitor to the Borders in Aventura just because they were so helpful.

Well, at least, I finally found Galeano in Buenos Aires.

At # 8:

At # 8:  At # 12 El entenado, Juan José Saer (1983)

At # 12 El entenado, Juan José Saer (1983)  At # 23

At # 23  At # 31 El pasado, Alan Pauls (2003)

At # 31 El pasado, Alan Pauls (2003)  At # 33

At # 33  At # 41

At # 41  At # 45

At # 45  At # 47 Plata quemada, Ricardo Piglia (1997).

At # 47 Plata quemada, Ricardo Piglia (1997).  At # 48

At # 48  At # 53

At # 53  At # 54 Los pichiciegos, Rodolfo Enrique Fogwill (1993)

At # 54 Los pichiciegos, Rodolfo Enrique Fogwill (1993)  At # 56

At # 56  At # 60. En estado de memoria, Tununa Mercado (1990)

At # 60. En estado de memoria, Tununa Mercado (1990)  At # 65

At # 65  At # 66 Una sombra ya pronto serás, Osvaldo Soriano (1990)

At # 66 Una sombra ya pronto serás, Osvaldo Soriano (1990)  At # 73 La muerte como efecto secundario, Ana María Shua (1997)

At # 73 La muerte como efecto secundario, Ana María Shua (1997)  At # 79 Glosa, Juan José Saer (Argentina, 1986)

At # 79 Glosa, Juan José Saer (Argentina, 1986)  At # 80 Crónica de un iniciado, Abelardo Castillo (Argentina, 1991)

At # 80 Crónica de un iniciado, Abelardo Castillo (Argentina, 1991)  At # 81 El traductor, Salvador Benesdra (2002)

At # 81 El traductor, Salvador Benesdra (2002)  At # 82 Cumpleaños, César Aira (2001)

At # 82 Cumpleaños, César Aira (2001)  At # 83

At # 83  At # 90 A sus plantas rendido un león, Osvaldo Soriano (1988)

At # 90 A sus plantas rendido un león, Osvaldo Soriano (1988)

One of my favorite historical topics is the intellectual and cultural history of the early twentieth century. Recently I’ve been reading a book titled Yrigoyen Entre Borges Y Arlt (1916 – 1930). It’s the second volume in a planned seven volume history of Argentine literature during the twentieth century. The series is edited by the writer David Viñas.

One of my favorite historical topics is the intellectual and cultural history of the early twentieth century. Recently I’ve been reading a book titled Yrigoyen Entre Borges Y Arlt (1916 – 1930). It’s the second volume in a planned seven volume history of Argentine literature during the twentieth century. The series is edited by the writer David Viñas.