October 2006

Monthly Archive

When I started working with the Cuban Heritage Collection at the University of Miami library I was surprised to learn about the Irish who had settled in Cuba. It was then that I realized I knew very little about the Irish diaspora even though the roots of my own family is partly Irish. While Argentina’s role in the Irish diaspora is not so widely known, the majority of the more than 40,000 Irish who came to Argentina in the second-half of the 19th century were from the Irish midlands.

Their journey took them first to the port at Liverpool where they board ships destined for Argentina. Most settled as sheep farmers in the area between Buenos Aires and Santa Fe. There’s even a small amount of literature influenced by these Argentine-Irish settlements.

More on the Irish in Argentina in later postings.

G.W. Ray was a 19th century North American missionary but he is remembered more for being a long rider, someone who traveled more than 1,000 miles on horseback in a single journey. Ray wrote about his experiences in South America in “Through Five Republics on Horseback: Being an account of many wanderings in South America.”

If you can get through his proselytizing and colonial attitudes (which are both laughable and sad), then you’ll find an intriguing work. In much of the book there is a sense that Ray used religion mostly as an excuse to justify his explorations. His journey began in Buenos Aires in 1889 when he arrived by steamer ship after a five week voyage from North America.

How shall I describe the metropolis of the Argentine, with its one-

storied, flat-roofed houses, each with grated windows and centre patio?…The Buenos Ayres of 1889 was a strange place, with its long, narrow

streets, its peculiar stores and many-tongued inhabitants. There is

the dark-skinned policeman at the corner of each block sitting

silently on his horse, or galloping down the cobbled street at the

sound of some revolver, which generally tells of a life gone out….At early morning and evening the milkman goes his rounds on

horseback. The milk he carries in six long, narrow cans, like

inverted sugar-loaves, three on each side of his raw-hide saddle, he

himself being perched between them on a sheepskin.”

Throughout the book is Ray’s love for horses. He describes this scene from late 19th century Buenos Aires:

One is struck by the number of

horses, seven and eight often being yoked to one cart, which even

then they sometimes find difficult to draw. Some of the streets are

very bad, worse than our country lanes, and filled with deep ruts and

drains, into which the horses often fall. There the driver will

sometimes cruelly leave them, when, after his arm aches in using the

whip, he finds the animal cannot rise….

As I have said, horses are left to die in the public streets. It has

been my painful duty to pass moaning creatures lying helplessly in

the road, with broken limbs, under a burning sun, suffering hunger

and thirst, for three consecutive days, before kind death, the

sufferer’s friend, released them….

I have said the streets are full of holes. In justice to the

authorities I must mention the fact that sometimes, especially at the

crossings, these are filled up. To carry truthfulness still further,

however, I must state that more than once I have known them bridged

over with the putrefying remains of a horse in the last stages of

decomposition. I have seen delicate ladies, attired in Parisian

furbelows, lift their dainty skirts, attempt the crossing–and sink

in a mass of corruption, full of maggots.

A few years years later

Ray contrasts those scenes of Buenos Aires in 1889 with the dramatic changes that took place in the city around the turn of the century.

The city, once so unhealthy, is now, through proper drainage, “the

second healthiest large city of the world.” The streets, as I first

saw them, were roughly cobbled, now they are asphalt paved, and made

into beautiful avenues, such as would grace any capital of the world.

Avenida de Mayo, cut right through the old city, is famed as being

one of the most costly and beautiful avenues of the world.

On those streets the equestrian milkman is no longer seen. Beautiful

sanitary white-tiled _tambos_, where pure milk and butter are sold,

have taken his place. The old has been transformed and PROGRESS is

written everywhere.

I was walking down the stairs of the apartment building the other day when one of the neighbors sighed and said that someone stole the brass handle to the front door. I’ve heard that happened a lot just after the economic crisis a few years back but didn’t know that it was still common. Obviously, the Argentine economy is not improving for everyone. It’s annoying but at least the thief didn’t damage the lock mechanism in the process.

Interested in South America and have a scientific bent? Then lose yourself for weeks among the complete work of Charles Darwin, now available online. It’s quite an astonishing collection pulled together by the University of Cambridge.

And if you don’t want to wade through all the texts and images, then you can download the mp3 audio versions. Yeah, that’s right, though I suggest not operating heavy machinery while listening to The effects of cross and self fertilisation in the vegetable kingdom. Seriously, though, it’s great that the audio is available for those with vision impairments.

Darwin spent a lot of time roaming around South America. Relevant readings include the 1830s voyage led by Robert Fitz-Roy. During that time Darwin visited Buenos Aires and the pampas where he made the following observation about the diminishing presence of Indians in the pampas:

Among the captive girls taken in the same engagement, there were two very pretty Spanish ones, who had been carried away by the Indians when young, and could now only speak the Indian tongue. From their account they must have come from Salta, a distance in a straight line of nearly one thousand miles. This gives one a grand idea of the immense territory over which the Indians roam: yet, great as it is, I think there will not, in another half-century, be a wild Indian northward of the Rio Negro. The warfare is too bloody to last; the Christians killing every Indian, and the Indians doing the same by the Christians. It is melancholy to trace how the Indians have given way before the Spanish invaders. Schirdel says that in 1535, when Buenos Ayres was founded, there were villages containing two and three thousand inhabitants. Even in Falconer’s time (1750) the Indians made inroads as far as Luxan, Areco, and Arrecife, but now they are driven beyond the Salado. Not only have whole tribes been exterminated, but the remaining Indians have become more barbarous: instead of living in large villages, and being employed in the arts of fishing, as well as of the chace, they now wander about the open plains, without home or fixed occupation.

From Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle round the world, under the command of Capt. Fitz Roy R.N 1845. A later publication of these journals is more commonly known as The Voyage of the Beagle. A bibliographical note states, “The best illustrated edition, in any language, is the Spanish of 1942, printed in Buenos Aires with 121 plates.” Now that’s something to track down at some rare book store around Buenos Aires.

Throughout the works are a lot of other fascinating insights about Argentina and other parts of South America.

One of the mysteries that I love about Buenos Aires is never knowing what is behind a building’s facade. Earlier I mentioned the enchanting bookstores on Esmeralda. Between Poema 20 and El Libro Frances is the door to an apartment building that appears to have a lovely courtyard.

Whenever I pass by this building, whether on a walk or on the 17 bus, I glance through the black iron grill of the doorway and wonder what’s inside. I recently learned that another well known BA blogger isn’t shy about talking his way inside buildings (you know who you are). I’m not quite that ingenious but recently Ceci and I were walking down Esmeralda when we noticed that the door to this building was slightly opened. So, we just decided to stroll inside, where some nice tiles line the entryway.

The building isn’t spectacular by Buenos Aires standards but it has a nice appeal. The entry leads down to a small courtyard with several, almost hidden, staircases sneaking off to the upper floors.

Looking skyward provides the most striking aspect of the courtyard: the immense amounts of glass that looms overhead gives the fairly small courtyard a refreshing feeling.

So now when I’m riding the 10 or the 17 bus from San Telmo to Recoleta, I no longer have to guess what waits behind the doors between those two bookstores on Esmeralda.

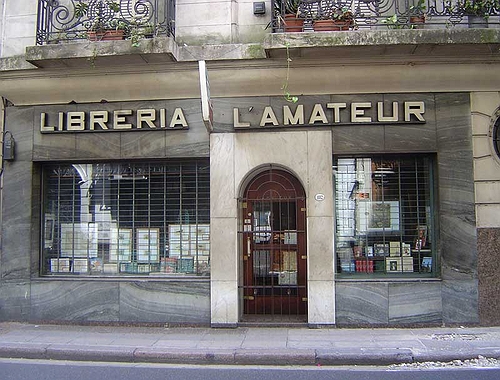

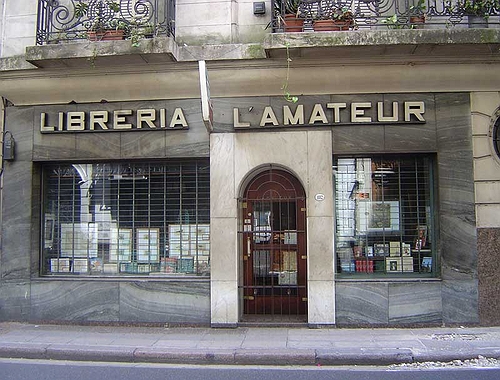

There’s something about bookstores that attract me, perhaps the adventure of never knowing what waits inside. Buenos Aires is full of bookstores and, downtown, on the 800 block of Esmeralda are three charming bookstores: Poema 20, Libreria Anticuaria L’Amateur, and El Libro Frances.

These booksellers all specialize in titles that you’re not likely to find elsewhere in the city. Whenever I get the chance, I try to stop by and gaze in the windows of these stores. Even when they’re closed and the iron bars are drawn down over the glass, I enjoy lingering in front of these stores, looking at the titles on display.

An interesting literary side note is that Argentine writer Alfonsina Storni once lived down the street in the beautiful building on the corner of Esmeralda and Córdoba.

Related post: last year’s antiquarian book fair.

A listing of the 30 Days with Borges series. Also, these and additional postings about Borges can be found under the Borges category.

There are a lot of hearts on display in Retiro, around Plaza San Martín and Palacio Paz. Like the Cow Parade and other similar displays the hearts are for a charity. In this case, appropriately, a heart foundation.

I don’t know how long the hearts will be hanging around, hopefully not that long but it makes a refreshing perspective on the area when it’s like your 300th visit to Plaza San Martín.

And if you like the hearts or even if you don’t, then you might be interested in this related post from my archives: Cheers for Italia from the heart patients…and for a great doctor

The other day walking down calle Marcelo T. de Alvear I saw a plaque on a building that I’ve never noticed before. The sign said that Uruguayan artist Pedro Figari (1861 – 1938) once lived in the building. I immediately remembered having seen some of Figari’s paintings in Montevideo.

The main reason I’ve never noticed the plaque before is that across the street is a view of the rear of Palacio Paz, which always attracts my eye. The location is off of calle Maipu, just down from the corner where Borges lived.

If you’re in the area, take a few minutes to wander down that block of Marcelo T.

An interesting article about Figari tells us a little about the avant garde in 1920s Buenos Aires.

In the same year that he [Figari] arrived in Buenos Aires, Jorge Luis Borges was returning to his native country after an absence of six years, bringing with him the experience of the Spanish Ultraismo literary movement. Two years later, Fervor de Buenos Aires appeared. Oliveiro Girondo published Veinte poemas para ser leìdos en el tranvìa, a forerunner of the literary renewal proposed by the Martin fierrista movement. Figari initially refused to follow this trend, but rediscovered it later on. Also in 1921, the Prisma editions were released. This mural magazine was the first of a long list of publications: Inicial (1923-27), Martin Fierro (1924-27), Proa (1924-26), Valoraciones (1923-28).

All of these publications clearly manifested a desire to confront everything that was European, even if the origins of those avant-garde movements had been founded on European literary and fine arts movements. Spain and Ultraismo, Italy and Futurism, France and Surrealism as well as the Dada movement.

Take a moment to check out a Google image search on Figari to get an idea of his paintings.

Update: May 25, 2010 – Teatro Colón is now re-opened after a 3 year renovation..

At the end of the month, Buenos Aires great opera house Teatro Colón will be closing its doors for a year and a half while the building is renovated. Teatro Colón is scheduled to re-open on May 25, 2008.

(Having been involved myself in a couple of major building renovation projects, I’m sure everyone managing the renovation of the Colón is worried about meeting that deadline. Already, even the announcement on the theater’s Web site says that Teatro Colón will re-open with “most of the works completed.” To see what’s going to be happening, take a look at the master plan for the restoration of Teatro Colón.)

Some history

Lately, I’ve been reading a lot about the history of Teatro Colón and opera in Buenos Aires, particularly the influence of Italian immigrants on the local opera scene. So, I’ve decided to create a series of postings, sort of a history of opera in Buenos Aires. I’m not yet sure how many postings will be in this series, but I’m going to try and keep the postings short: nuggets of information rather than encyclopedic. Anyone with more knowledge about any of these topics, please jump in with comments. I’m just learning these things as I read, passing along what’s interesting.

A brief history of Teatro Colón itself is available on its Web site. (That same link is available in Spanish).

While the present Teatro Colón will celebrate its 100th anniversary in 2008, there actually was another Teatro Colón that was built in 1857 across from Plaza de Mayo, where the Banco de la Nación is located. The first Teatro Colón closed in 1888. While the new Teatro Colón was being built over the following 18 years, the dominant opera house in Buenos Aires was Teatro de la Ópera, which was built in 1872. Another theater of that time was Teatro Politeama, which remained popular well into the 20th century. The Politeama wasn’t just an opera house, but provided a venue for a lot of popular entertainment. Have a look at this Yiddish poster advertising a show at the Politeama in the 1930s.

Okay, I promised to keep these postings short, so I’m stopping now…need to come back another day and say something more about the Teatro de la Ópera.

Next Page »