I spent some time today playing around with a very cool interactive map of Buenos Aires developed by the city government. Warning: you can find yourself wasting a serious amount of time.

By default the site will give you a street map with outlines for each lot. You can zoom around and focus in on detailed sections, just like other mapping tools. One obvious reason for the system’s creation was GIS-based management of property in the city. Select the option labeled datos inmobiliarios, then click on any lot and a pop-up window will display a photo and basic info about the building on that location (size, permitted uses, etc.).

I often use the city’s Patrimonio site, which has its own features but the two geo-based services don’t yet seem to be linked together. There’s a lot of interesting historical data in the Patrimonio database and having these two systems linked would be handy….maybe that’s in the works for the future.

Photographic Overlays

But the feature I really like is when you select the option imagenes y fotografias from the left navigational panel. From here you get several options:

- 2004 color satellite images

- 1978 aerial photographs

- 1965 aerial photographs

- 1940 aerial photographs

I got very excited at the historic aerial photographs of Buenos Aires. This is a great way to see how the city has changed over the decades. (See my city that fades away series for more on that topic).

I’ll have some future postings about specific buildings and places that I’ve observed have changed but for now let’s examine one of the most known (and destructive) changes in the city.

Av 9 de Julio

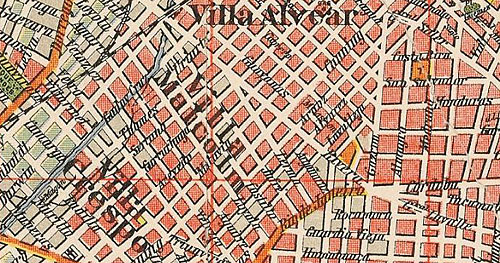

A swath of the city was demolished for the construction of Av 9 de Julio. In the 1940 aerial photo below we can see that Av 9 de Julio at that time stretched only from the streets Tucuman to Mitre…rather tiny by today’s comparison.

Notice how the 1000 block of Av de Mayo is still intact. But by 1965 Av 9 de Julio stretched as far south as Belgrano. (I’ll leave exploring the northern boundary of Av 9 de Julio for your own exploration in the mapping system).

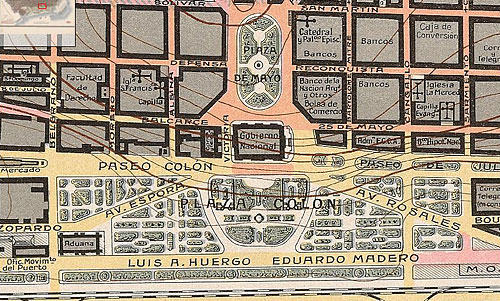

Av 9 de Julio & Constitución

In 1940 the broad avenue had not yet swept into the southside of Buenos Aires. The area around Constitución station appeared fairly pleasant. Indeed, the house of a former president (Yrigoyen) of Argentina was located on the 1000 block of Av Brasil, the block pictured in this photo. So you have to use your imagination to picture what this part of the city looked like sixty some years ago, a neighborhood very different from today.

But look at the 1978 photo. That very block has been replaced by a huge parking lot.

And now passing over the parking lot is an overpass.

I do have to say that the city is current working on improving this area around Constitución station and under the highway. There is still the parking lot but they are planting trees, bushes, widening the sidewalk and making it all appear nicer or, at least, as nice as you can make an area under a highway.

Technical Note

The site loads very slowly but wait a few seconds and it should appear. Once it’s initially loaded then it operated at normal speeds for a mapping site. There is supposedly a way to link directly to the views within the interactive map of Buenos Aires but I couldn’t figure that out. (Thanks to the All Points Blog for mentioning the mapping site).