September 2005

Monthly Archive

This post isn’t about Buenos Aires specifically but anyone interested in Spanish literature knows that 2005 is the 400th anniversary of the publication of Don Quixote. Go to a bookstore in Buenos Aires and you can’t miss it.

A number of editions are available. For English language readers, picking the right translation sometimes can be a challenged. Earlier this year I was browsing in a Barnes & Noble in Miami and came across the classic book section. Prominently displayed in a new edition, published by Barnes & Noble, was Don Quixote. The first thing I do when picking up any translated book is to check the name of the translator. This edition of Don Quixote was translated by Tobias Smollett. I found it quite funny that Barnes & Noble would promote an 18th century translation of what many call the world’s greatest novel. Of course, Barnes & Noble probably could get the rights to that version since that version is likely in the public domain. I feel sorry for the readers who choose the Smollett translation with its rather antiquated style. They probably will end up hating Quixote and will never understand what all the fuss is about. From the Amazon’s reviews of the Smollett translation there are obviously some people who like it, though I suspect that they haven’t examined the other translations too closely.

Yet, Smollett’s version is one of the most known English translations due to its wide availability, which perhaps explains why Don Quixote has never been particularly popular in English except mostly among those who study literature. There’s even an entire niche discipline in literary studies that focuses on nothing but English translations of Cervantes. Indeed, it’s a great example for comparative study of the issues involved in translation.

The translation that is getting all the attention this year is the new one by Edith Grossman , one of the best translators working today. Incidentally, Grossman got her start in this field by translating a story by Macedonio Fernández, a little known Argentine writer greatly admired by Borges. After translating Love in the Time of Cholera

, one of the best translators working today. Incidentally, Grossman got her start in this field by translating a story by Macedonio Fernández, a little known Argentine writer greatly admired by Borges. After translating Love in the Time of Cholera by Gárcia Márquez, she started translating full-time. Some of Grossman’s other translations include five other works by Gárcia Márquez, whom she says is harder to translate than Cervantes. She also has translated numerous works by Vargas Llosa, as well as dozens of books other Spanish language writers.

by Gárcia Márquez, she started translating full-time. Some of Grossman’s other translations include five other works by Gárcia Márquez, whom she says is harder to translate than Cervantes. She also has translated numerous works by Vargas Llosa, as well as dozens of books other Spanish language writers.

Grossman offers this advice to translators:

“Fidelity is surely our highest aim, but a translation is not made with tracing paper. It is an act of critical interpretation. Let me insist on the obvious: Languages trail immense, individual histories behind them and no two languages, with all their accretion of tradition and culture, ever dovetail perfectly. Fidelity is our noble purpose, but it does not have much, if anything, to do with what is called literal meaning. A translation can be faithful to tone and intention, to meaning. It can rarely to be faithful to words or syntax, for these are peculiar to specific languages and are not transferable….To re-create significance for a new set of readers, translators must make the effort to enter the mind of the first author through the gateway of the text – to see the world through another person’s eyes and translate the linguistic perception of that world into another language. The better the original writing, the more exciting and challenging the process is.”

To learn more about Grossman see “At the Service of Language”, Bach, Caleb. Américas. Dec 2004, p 24.

If you’re embarking on your own reading of Don Quixote then you should definitely take a look at 400 Windmills, a group blog dedicated to discussing Don Quixote.

Anyone interested in cultural and historical topics about Latin America should consider subscribing to the magazine published by the Organization of American States, Américas. There are both English and Spanish editions of the magazine. I brought with me a large number of articles from it that are related to Argentina when I moved here. In future postings, I’ll try to summarize some of them.

Times are getting more and more difficult for translating literature into other languages, particularly English. Basically, it’s a business issue. English language publishers see a limited market for translated works and so just focus on a narrow set of the biggest name writers. Almost anyone can name the list: Garcia Marquez, Borges, Cortazar, Fuentes, Allende, and Vargas Llosa are at the top of the list followed by just a small handful of others. The problem isn’t limited to Spanish works. Indeed, Spanish is likely very well represented when compared to most other languages. However, a significant amount of the global culture is being marginalized through the inaccessibility of literature in translation.

Jeremy Munday, now Deputy Director of the Centre for Translation Studies at the University of Surrey, wrote an article in the mid-90s that examines these issues. Things haven’t improved and the same article could just as well have been written now rather than ten years ago. Munday closes with an observation about Venezuela, but his statement could apply to the literature of most of the world:

“The possibility exists, therefore, that these particular voices and the culture of a whole country will remain silenced, marginalized, unable to communicate outside their own language. The vicious distorting circle persists of insular English-language readers, of publishers unable or unwilling to take a risk, the concentration on a few ‘safe’ writers.”

I stumbled across this excellent essay by David Rock titled Racking Argentina that provides a solid background for understanding today’s current economic conditions in Argentina.

David Rock is the leading English-language historian of Argentina and his work always has an economic slant to it. While written in 2002 before the election of Kirchner, the article is still timely as David Rock puts the situation into a global context, explaining how economic conditions in various parts of the world impacted the Argentine economy. He also points out critical mistakes by the government: “During the Menem years, investment potential remained largely in the imagination of the president’s advertising team.”

Buenos Aires is simply full of fascinating buildings. Around the corner from our apartment is this old Quilmes beer distribution facility.

Borges had fostered an intense dislike for Perón for years. The latest biography of Borges ( Borges: A Life ) recounts the story that the writer told about his reaction to the coup that toppled Perón:

) recounts the story that the writer told about his reaction to the coup that toppled Perón:

Borges immediately phoned his sister to break the news to his familly. Then he went out again; the entire population of the Barrio Norte seemed to have surged into the streets to celebrate the news of Perón’s downfall. It was pouring rain, but no one minded – there were crowds everywhere, wandering about aimlessly, singing and shouting. Borges himself was deliriously happy and kept crying out “Viva la patria!” at the top of his voice. He ran into a girl he knew on calle Libertad, and by the time they had found their way back to the avenida Santa Fe, he was soaked to the skin and had lost his voice with all the shouting. “I remember the joy we felt; I remember that at that moment no one thought about themselves: their only thought was that the patria had been saved.(p.328)

Unfortunately, Argentina didn’t fare too well under its new government either and Borges’ political optimism didn’t last long. Yet, Borges himself benefited from Perón’s downfall when, a few weeks later, Borges was named director of the National Library.

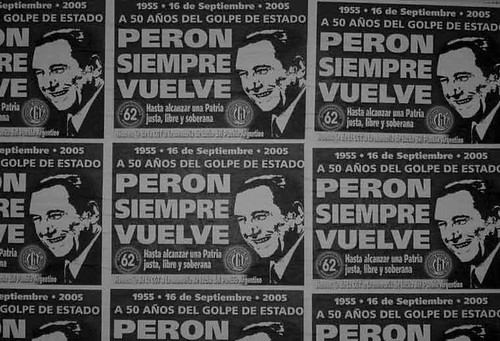

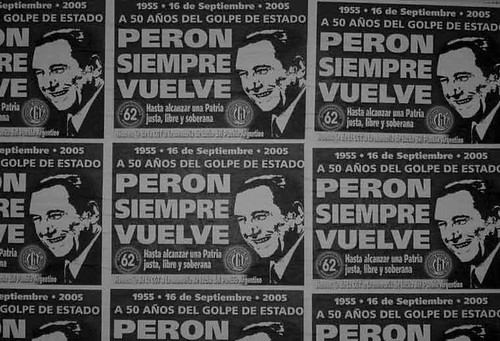

September 19, 2005 is the 50th anniversary of the coup that ousted Juan Perón from power. Evidently, from these posters, some people just haven’t gotten over that.

Perón had been president from 1946 – 1955 and was the dominant figure in the government for several years before becoming president. Afterwards, he lived in exile and briefly returned as president in the early 1970s before dying in 1974.

Argentine political history is complicated and the popularity of Perón is one of the more difficult topics to understand. The nature of modern Peronism, especially the current split in the Peronist party, adds to the confusion….but that’s another post entirely.

Perón’s power had been weaking for several years before his downfall in 1955. Much of Perón popularity was in the form of his wife, Eva, who died of cancer in 1952. The country also was in an economic crisis in 1952. The economy had essentially stopped growing due to various miscalculations by the government over a number of years. The urban working population expanded but the manufacturing sector didn’t have enough jobs to accomodate the expanded workforce. Social protests resulted in a large number of strikes in 1954.

(The posters in the photo were put up by the CGT [Confederacíon General del Trabajo] the major labor union, which always was a significant supporter of Perón. (Of course, the history and present status of Argentine labor unions and the working class is yet another extremely complicated topic).

As conditions worsened in the early 1950s Perón became more authoritarian. His clash with the Roman Catholic Church resulted in the Church becoming a symbol of opposition to his government. Also the military became more restless with Perón as high-ranking officers started to glimpse opportunities to grab their own share of the power; Perón himself had achieved political success through his own military career

One of the most tragic episodes in Argentine history was June 16, 1955. Perón supporters were rallying in Plaza de Mayo when navy planes started to drop bombs in an attempted coup. It is really a shocking event that the military could bomb its own people. (Yet, more attrocities from the Argentine military would be coming in future decades). The coup failed but Perón basically had lost power and was hanging on thanks only to the support of the army, which hadn’t yet totally turned against him. For a few months in the middle of 1955 Argentina was on the verge of civil war. The army finally turned against Perón on September 16 with rebellions in Córdoba and Bahia Blanca. Perón resignation came on September 19, 1955.

I mentioned in my earlier posting about the Night of the Pencils march that la Pirámide de Mayo became a target for creative political expression on Friday evening. Photos of the other sides of the piramide are on my flickr site. Wonder how long till the government paints it?

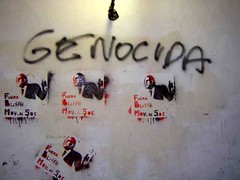

This appeared on the front wall of the Cabildo during Friday night’s march. More graffiti that appeared on the Cabildo that night can be found on my flickr pages. I’ve not used flickr much, so I don’t have things organized very well on there yet. For this posting, I tried flickr’s “blog this” feature, which allows you to blog directly from your flickr account to your own blog…it worked pretty well! May have to make more use of that.

On September 16, 1976 seven teenagers in La Plata were kidnapped by the government for protesting bus fares. Only one of the teens survived, the rest became part of the disappeared. Known as the Night of the Pencils it is one of the many infamous acts that occurred during Argentina’s last military dictatorship. Tonight, the 29th anniversary, a massive march was held in downtown Buenos Aires to commemorate the event. There also was a social agenda to the student marchers, the demand of wage and budget increases in the educational sector.

Early in the day there was some concern about the march as the government announced the previous night that police would again block parts of Avenida de Mayo and restrict marchers to a specified route in order to reach Plaza de Mayo. Last Friday night’s march became a tense standoff between marchers and the police. It seemed like there was the possibility for more of the same. However, midday Friday, the government changed its mind and announced that marchers would be free to walk all the way down Av de Mayo from Congreso to the Plaza. The opening of Av de Mayo was mediated by Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1980 for his efforts to promote human rights in Argentina and Latin America.

Compared to last week, this evening’s march was very peaceful. Along Avenida de Mayo there were hardly any police, though a significant police presence encircled the Catedral side of Plaza de Mayo. A metal fence was erected alongside the Plaza to keep traffic flowing freely along Rivadavia, which runs westbound on the north side of the Plaza. Even in front of the Palacio Municipal (the “city hall”), often a focal point of protest for the city’s frustrated, there was only a small contingent of riot police positioned behind two metal fences that stood between them and the marchers. But, that’s hardly an unusual sight at the home of city government.

It was one of the largest marches that I have seen in Buenos Aires. Considering the tensions of last week surrounding access to Plaza de Mayo, it seems as if every group that regularly protests social issues turned out for this event. Ceci and I first watched the start of the march from a spot near Congreso across from La Inmobiliara. Once all the student groups had passed we quickly made our way down to the other end of Av de Mayo and positioned ourselves between the Cabildo and Palacio Municipal. For more than ninety minutes, group after group, each carrying their own distinctive banners and flags, marched by. Every so often, a group would stop in front of Palacio Municipal to shout and chant angry slogans at the city and to taunt the police behind the barricades.

The crowd was so large that the rally in the Plaza ended before all the marchers could arrive there. Since the police had blocked off the roads north of the Plaza, most people simply returned to Av de Mayo and marched back towards Congreso. This created a rather odd sight as you had a flow of marchers still arriving and another stream of them departing all along the same street.

The Cabildo and the Pirámide de Mayo suffered extensive graffiti coverage, most of which was of an anti-Bush nature. (Dubya is coming to Argentina in November). Remember that last week’s protest was supposed to be an anti-Bush march, but since the marchers never made it to Plaza de Mayo last week I guess they were saving their graffiti for tonight.

The crowd cleared out of Plaza de Mayo fairly quickly after the rally. Afterwards, it was mostly just small groups of students hanging around, dancing, and smoking.

Next Page »

, one of the best translators working today. Incidentally, Grossman got her start in this field by translating a story by Macedonio Fernández, a little known Argentine writer greatly admired by Borges. After translating Love in the Time of Cholera

by Gárcia Márquez, she started translating full-time. Some of Grossman’s other translations include five other works by Gárcia Márquez, whom she says is harder to translate than Cervantes. She also has translated numerous works by Vargas Llosa, as well as dozens of books other Spanish language writers.