July 2005

Monthly Archive

A book I’ve been reading lately is The Jewish Gauchos of the Pampas [Los Gauchos Judíos] by Alberto Gerchunoff. Through a series of 26 interlocking stories it conveys the history of Russian Jews who emigrated to Argentina. Set in Entre Rios province this small book creates a vivid picture of the life in the Jewish farm settlements. Gerchunoff’s own grandfather was one of the original Jewish colonists in Argentina. This book was first recommended to me by a Jewish colleague of mine in Miami who grew up in Rosario. She said that the stories in this book remind her of the stories that she heard as a young child in Argentina.

[Los Gauchos Judíos] by Alberto Gerchunoff. Through a series of 26 interlocking stories it conveys the history of Russian Jews who emigrated to Argentina. Set in Entre Rios province this small book creates a vivid picture of the life in the Jewish farm settlements. Gerchunoff’s own grandfather was one of the original Jewish colonists in Argentina. This book was first recommended to me by a Jewish colleague of mine in Miami who grew up in Rosario. She said that the stories in this book remind her of the stories that she heard as a young child in Argentina.

Undoubtedly, while reading the book I came away with a sense of the heritage that the families brought with them to their new country. The importance of faith and ritual is stressed. Even on the farm the plowing of the first furrow in the field is given not only symbolic significance but is an act respectfully observed by the entire family. Yet, as I read I couldn’t help but wonder if these first generation immigrants from Russia wondered what were they doing here, in Entre Rios, in South America? Towards the end of the book one of the stories is about an old colonist Reb Guedali ben Schlomo. Possessing the “noble bearing” of the highly educated, Guedali served as a teacher to the narrator. As a young man, Guedali was a rich landowner. In what was still a feudalized Russian society, Guedali had socialist ideas and shared the product of his lands with those who worked it. The young narrator learns through Guedali not to question his new homeland but to be thankful:

Guedali “had journeyed to Jerusalem before, but he had returned saddened, and declared that he preferred to live in any place but the crowded square that was the sacred capital of the Jews, with its convents, its crosses and its minarets. He came to Entre Rios with the first immigrants. Here, he had realized his ideal, to work the land, to eat bread made from his own wheat and beans grown in his own garden.”

An excellent fiften page introduction accompanies the English translation of the Jewish Gauchos of the Pampas. Originally published in 1910 the Jewish Gauchos of the Pampas has been called the first significant literary work in Spanish written by a Jew. The National Yiddish Book Center in the U.S. has the book on its list of the 100 Greatest Works of Modern Jewish Literature.

In 1975 Los Gauchos Judíos was made into a movie of the same name. It would be remiss of me not to mention that a couple parts of the book (at least, the English translation) do read rather like a telenovel:

“Meanwhile, by the little stockade, Raquel went on milking the quiet cow. She was on her knees as her fingers squeezed the magnificant udders and pressed out streams of steaming milk. The dawn around them now was the pale red of autumn, but the open neck of Raquel’s dress showed full firm breasts that a hot summer sun had baked the color of golden fruit. The milk squirted into the pail with the same soft rhythm as the girl’s breathing and the light snorting of the cow.”

I’m wondering how they filmed that scene.

The Jewish gauchos also have been the subject of a 1990 documentary by two filmmakers from the U.S., Mark Freeman and his wife Alison Brysk. Freeman tells the very interesting story behind the making of his documentary Yidishe Gauchos in this essay titled Fiddler on the Hoof: The Jewish Gauchos of Argentina.

Writer Jeremy Sheldon, author of the new novel The Smiling Affair, was asked by the Guardian to prepare a list of his Top 10 Supernatural Books. In the list at the number 4 spot is Julio Cortázar’s short story Bestiary. Available in English in the collection Blow-Up : And Other Stories or in Spanish, Bestiario

or in Spanish, Bestiario .

.

One of the pleasures of living here in Buenos Aires is encountering novelists and poets that have been unknown to me. Almost each day I seem to “discover” an Argentine writer, or Spanish language author, that brings a new perspective to my now seemingly narrow literary world. Yet, I’ve always considered myself well-read. When I was an undergraduate at Sewanee I majored in English and American literature and took eight college-level courses in Russian, four focused primarily on 19th-century Russian literature. But, why am I so unaware of writers in the Spanish language?

Of course, I learned about Borges as an undergraduate, though not actually as part a course syllabus. It was in a conversation with my freshman English teacher Cheri Peters who recommended Borges to me, particularly the selections known in English as Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings  . We had been given a writing assignment on a short story by either Robert Coover or another author from the Norton Anthology. It turns out that I was the only student in that particular class who chose Coover’s “the Babysitter” over the other story, which I now forget. Most likely the other students found Coover’s disturbing sexual storyline about the babysitter too embarrassing to write an essay about. I don’t know why I didn’t, considering that I was incredibly shy at the time. But, it was the unusual narrative approach of Coover that really intrigued me. (And, well, the story is pretty good itself!) Anyway, when Dr. Peters discussed the paper with me (my essay wasn’t anything spectacular, by any means) she mentioned that if I liked Coover’s style then I should read the stories by Borges in Labyrinths. A year or so later I remember my college friend David, who was from Puerto Rico, telling several of us about Borges and that we should read Borges before he died. David’s comment reminded me of Dr. Peters recommendation. So I went to the library at Sewanee and read my first Borges. The great Argentine writer would die midway through my undergraduate studies. Little did I know at the time that I would someday be living in Buenos Aires and walking his beloved streets for myself.

. We had been given a writing assignment on a short story by either Robert Coover or another author from the Norton Anthology. It turns out that I was the only student in that particular class who chose Coover’s “the Babysitter” over the other story, which I now forget. Most likely the other students found Coover’s disturbing sexual storyline about the babysitter too embarrassing to write an essay about. I don’t know why I didn’t, considering that I was incredibly shy at the time. But, it was the unusual narrative approach of Coover that really intrigued me. (And, well, the story is pretty good itself!) Anyway, when Dr. Peters discussed the paper with me (my essay wasn’t anything spectacular, by any means) she mentioned that if I liked Coover’s style then I should read the stories by Borges in Labyrinths. A year or so later I remember my college friend David, who was from Puerto Rico, telling several of us about Borges and that we should read Borges before he died. David’s comment reminded me of Dr. Peters recommendation. So I went to the library at Sewanee and read my first Borges. The great Argentine writer would die midway through my undergraduate studies. Little did I know at the time that I would someday be living in Buenos Aires and walking his beloved streets for myself.

The bombings in London also remind me how I became aware of two other significant Argentine literary figures, people who played an important role in Borges’ life: Norah Lange and Oliverio Girondo. It was last September and we had gotten a good rate through Priceline at the Novotel London Euston hotel, which overlooks the British Library. Earlier in the week I had given a presentation at the Digital Resources in the Humanities conference in Newcastle. After the conference Ceci & I went up to Edinburgh for a few days then took an EasyJet back to London. As a discount airline EasyJet lands in Luton rather than Gatwick or Heathrow, so we took the Thameslink train from the Luton station to King’s Cross – the same train into London that the bombers took on the morning of July 7.

Relaxing in the hotel I vividly remember reading the literary section of the Guardian and was delighted to read about a new biography of Borges by Edwin Williamson was being published (Borges: A Life ). The Guardian was running an excerpt Moth to the Flame that told how Borges’ infatuation with the poet Norah Lange impacted him. I immediately asked Ceci if she had heard of this Norah Lange. Ceci asked, “How do you spell her name?”. I replied, “L-A-N-G-E”. She answered, “Oh, yes, but the name is pronounced ‘Lan-hay’ and not ‘Lang’ as it would be in English.”

). The Guardian was running an excerpt Moth to the Flame that told how Borges’ infatuation with the poet Norah Lange impacted him. I immediately asked Ceci if she had heard of this Norah Lange. Ceci asked, “How do you spell her name?”. I replied, “L-A-N-G-E”. She answered, “Oh, yes, but the name is pronounced ‘Lan-hay’ and not ‘Lang’ as it would be in English.”

According to Williamson’s 500 page biography, Borges was fascinated by the redheaded Norah Lange and spent countless hours in her company though it’s never really clear to what extent she returned his affections. Certainly, she was his close friend and admired his intelligence. But it seems like the classic case of unrequited love – the shy, awkward guy yearning for the woman always just beyond his grasp.

It turns out that Norah was the center of a conflict between Borges and Oliverio Girondo. Before reading the Guardian piece, I also was unaware of Girondo. I asked Ceci about him and she proceeded to tell me that Oliverio Girondo was a very important figure in 20th century Argentine literature. Sometimes I feel ignorant for not knowing these things. But I just did a Google search on Oliverio Girondo and in the first five result pages only 1 entry is in English: the Oliverio Girondo Collection in the Rare Books and Special Collections of the University of Notre Dame library.

Borges introduced Lange to Girondo in 1926 at a party by the lake in the park in Palermo. For years a rivalry would ensue between Borges and Girondo, not just over Norah but over the literary leadership of Buenos Aires. One of the great things about Williamson’s biography is that it reminds the modern reader that Borges’ fame and popularity only occurred rarely late in his life. Through the 1920-1940s Borges was recognized as a writer but certainly not of the exalted stature that he would later achieve.

Indeed, one of Williamson’s main points is that Borges’ development as a fiction writer was intertwined with his love for Norah Lange:

“Since being rejected by Norah at the end of 1926, he had gradually lost his voice as a poet and had turned to essay writing to start with and then, very tentatively, to fiction, but his ideas had not yet cohered into a new aesthetic.” (Williamson p.192)

The relationship between Lange and Girondo was not an easy one. Borges knew this and continued his own attempts at winning Lange’s heart. Indeed, Lange and Girondo had an on-again, off-again relationship for eight years until 1934 when their relationship became stable, even though Girondo would not marry Lange for another nine years – on July 16, 1942.

Borges “had looked to Norah as the muse who would take him beyond the adventure of the avant-garde to the high summer of mature achievement, and for a while, in that annus mirabilis that was 1926, it appeared that his courtship of Norah might yet raise him to a high plane of happiness where his pen would blaze in the Whitmanesque ecstasy of communing at last with the essence of the world. But the collapse of that dream had cast him into a void from which he had found it impossible to emerge. Time and again since 1929 he had tried, and failed, to give an account of his experience with Norah and Girondo in his writing. The truth was that for so long as he failed to understand why he had lost Norah, he would remain enslaved to her memory, trapped in a circle of nostalgia and frustration. it was only by burrowing down to the roots of his private suffering that he would discover the true subject matter of his writing, and in the last months of 1937, his life took such a wretched turn for the worse that, after a troubled gestation of nearly ten years, he would be born at last as a writer of fiction. (Williamson p 229).

The section in the Guardian isn’t so much of an extract or even an excerpt from the biography as it is a summary of the chapters that deal with Borges, Lange, and Girondo. The biography itself is extremely well-written, very readable, and worth reading by any admirer of Borges. While the biography by Williamson has received some criticism for delving too much into a biographer’s psychoanalytic conjecture about Borges innermost thoughts and feelings, I found the interpretation by Williamson to be very insightful. Williamson, who is the King Alfonso XIII Professor of Spanish at the University of Oxford, also provides critical analysis of many works by Borges and attempts to demonstrate how certain works relate to significant events in Borges’ life. A critic could rightly argue that such a psychological undertaking is not the role for a biographer. But as I come to know Buenos Aires and its residents more and more each day, it seems to be the nature of many Porteños to reflect on psychoanalytical perspectives.

Williamson clearly admires Borges and his biography attempts to demythologize the writer so that the reader can see Borges not just as a wise, elderly, blind scholar who loves books but as a young man with all his insecurities and his own self-doubts that he struggles with in order to bring meaning to his life.

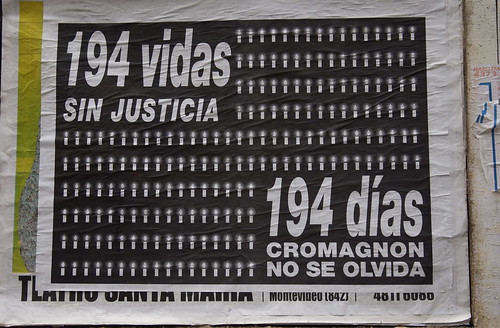

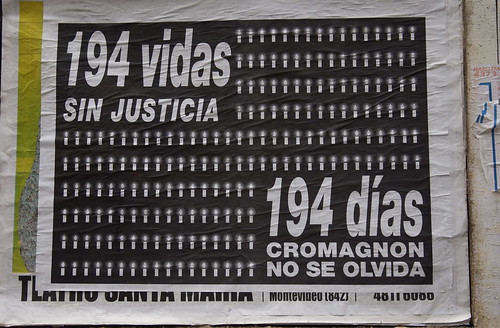

I was walking around Av de Mayo this afternoon when I noticed that this poster had sprung up around the downtown area. It’s a poignant reminder about the lack of justice for the 194 lives lost in the Cromagnon fire, 194 days ago.

The balcony of our 11th floor apartment overlooks the neighborhood of Once. The area is characterized as being predominantly Jewish and as the garment district of Buenos Aires. From our balcony, looking a couple of blocks to the east, we can see the only new building in the area: the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina (AMIA).

Located on calle Pasteur AMIA was the target of a terrorist bomb on July 18, 1994 that killed 85 and wounded hundreds. The AMIA attack came two years after a terrorist bomb also destroyed the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires. An incident in which killed 29 and wounded over 200.

In this age of terrorism these attacks are little known in North America. They happened before Oklahoma City, before 9/11. They happened back when terrorism was something that happened in countries outside the US. Unfortunately, they happened before the world became outraged over terrorism. Or, as someone in Buenos Aires said yesterday, people in the US and Europe didn’t care then because “terrorism happened to someone else”.

The attacks on AMIA and the Israeli embassy have never been solved, culprits have not been clearly identified, no one has been prosecuted. Little seems to have been done. Yesterday, a sticker was placed over the calle Pasteur street sign, temporarily renaming it calle Injusticia.

Monday morning, a memorial service was being held in front of the new AMIA building. Ceci and I decided to walk over there. Streets were barricaded several blocks in each direction by armored vehicles and heavily armed, masked soldiers in camouflage with automatic rifles at the ready. In addition to the armed troops, a multitude of regular police were joined by a large number of plain-clothed Jewish security agents. It was the most intense security that I’ve seen at anytime in Buenos Aires.

When we approached the barricades it didn’t appear that they were letting everyone through. We were directed by the police over to one of the Jewish security agents who questioned us about why we were there. He asked Ceci if she was part of the Jewish community. She replied that she was but that I wasn’t Jewish. He asked about her ties to the community and she mentioned that she used to own a shop in Once. Then he asked where she went to synagogue. She replied that she didn’t anymore but she had gone to synagogues in Once when she had the store there. Then he asked specifically which synagogues. Finally, he asked her family name. After she said “Sorochin”, he let us go through the barricade and then we were examined by the police for weapons. Somehow, I sense that I would not have gotten in by myself. Yet, with the recent bombings in London, the intense security was understandable.

The crowd gathered on calle Pasteur in front of the AMIA building and spread out into the adjoining intersections. Loudspeakers broadcasted the voices of the speakers out along the street. From our position at the corner of Pasteur and Tucuman, we couldn’t really see the speaking platform. The crowd was very quiet and somber, as expected. Glancing up at the buildings, I noticed that security agents were positioned on the top floor of the buildings and were scanning the crowd with binoculars.

When I moved here one of the first things I noticed when walking down calle Pasteur was the young trees that line the street. There are 85 trees in fact on Pasteur between Cordoba and Corrientes, one representing each life that was lost the day of the bombing. A plaque at the base of each tree commemorates those who died…David Barriga…Jacoba Chemauel…Monica Feldman De Goldfeder…on its web site, AMIA names the dead. Eventually, the trees will grow large, creating a beautifully shaded street.

Julio Cortázar (1914-1984) is one of the towering figures of Argentine literature. Yet, Cortázar is hardly known in the English speaking world even among the very well educated. Generally, only the most literary of English language readers will be familiar with Cortázar. Archipelago Press in the U.S. recently released the first English translation of the Diary of Andrés Fava, translated by Anne McLean.

Julio Cortázar (1914-1984) is one of the towering figures of Argentine literature. Yet, Cortázar is hardly known in the English speaking world even among the very well educated. Generally, only the most literary of English language readers will be familiar with Cortázar. Archipelago Press in the U.S. recently released the first English translation of the Diary of Andrés Fava, translated by Anne McLean.

An excellent article by Jessa Crispin in The Book Standard discusses the translator’s challenge in broadening awareness of Cortázar:

“‘In decent bookshops you see Hopscotch and Blow-Up, and in really good ones, you might find a few more. But he has become an obscure author in English, which Spanish and Latin American readers find pretty hard to believe.’

‘On the one hand,’ she continues, ‘it is a great shame that more of his work isn’t in circulation in English, but it also means there are many, many readers who still have the discovery of Cortázar to look forward to, and that’s something I envy. I think a Julio renaissance is long overdue, and it could be time to look at re-translating a lot of his early stories.'”

I first saw mention of this article over at the MoorishGirl, which I think is one of the best literary weblogs. As MoorishGirl says, “When I came to the States, I was surprised to find out how little of world literature people seemed to read. And things aren’t improving, with literature in translation being constantly curtailed to make room for the Da Vinci Codes and Harry Potters.”

With the largest Jewish population in Latin America Buenos Aires has 50 Orthodox synagogues, five Conservative, and one Reform . Eighty percent of Argentine Jews live in the capital. The World Jewish Congress estimates that the current Jewish population in Buenos Aires is 200,000, down from 300,000 over the past 40 years. Those who left have gone mostly to Mexico City, Miami, Spain, and Israel.

The World Jewish Congress also provides interesting details into Argentina’s Jewish communities.

My interest in Jewish immigration to Argentina is partly personal. Ceci’s father’s family, Sorochin, is Jewish. Her father was born in Paraguay to a Russian father and a Romanian mother. The couple had previously lived in Argentina. When he was young child they moved to Buenos Aires.The specifics of their story is mostly lost but there’s a clear pattern to Jewish immigration to Argentina that is well documented.

The Jewish Colonizatin Association was founded in 1891 by Baron Maurice de Hirsch and his wife in memory of their son. The Argentine government of that age viewed immigration as a favorable way of improving the quality of the country. Baron Hirsch purchased land throughout the world including over a million acres in Argentina.

Violent persecutions, known as pogroms, of Jews in Russia was taking place in the late 1800s.

Russians were not the only Jewish settlers in Argentina. Jews from Morocco, Syria, and other Sephardic communities also came to Argentina. World War II also saw a large influx of Jews to Argentina.

The Jewish Encyclopedia provides an excellent overview of the Jewish agricultural colonies in Argentina.

The Virtual Jewish History Tour provides brief insights into the Jewish community of Buenos Aires.

Those wanting to research their Jewish heritage in Argentina should start with the Asociación de Genealogía Judía de Argentina.

The San Diego Jewish Journal published a charming article by a woman in the US whose aunt somehow ended up in Buenos Aires rather than Brooklyn.

This week AMIA, the Jewish Community Center is Buenos Aires, is commemorating the 11 year anniversary of the bombing of AMIA that killed 85 people. In memory of that tragedy I’m posting a series of blog entries this week about the Jewish community in Buenos Aires.

With the massive immigration to Argentina in the late 1800s, different ethnic groups tended to congregate in specific neighborhods. Here’s a sample of generally who lived where in 1880 Buenos Aires: Italians favored La Boca; Spaniards were found in Monserrat, San Cristóbal, San Nicolás, and Constitución; the Syrians and Lebanese congregated around Retiro; Jews and Russians in Once. (Source).

This week AMIA, the Jewish Community Center is Buenos Aires, is commemorating the 11 year anniversary of the bombing of AMIA that killed 85 people. In memory of that tragedy I’m posting a series of blog entries this week about the Jewish community in Buenos Aires.

As most people know, the international Jewish community is remarkably strong. I found this nice little article from the Kansas City Jewish Chronicles about a young college student from Kansas who traveled to Argentina to experience Judaism in South America:

“We spent our first Shabbat in the Jewish colony of Avigdor, established in 1936 to house Jews fleeing from Germany. This was an incredible experience. On Friday night, as we entered the small yet beautiful temple, we were joined by members of the community and some of their relatives visiting from Israel. This is when so many of us realized the beauty of Judaism. Here was a group of Americans, Argentines and Israelis who connected as Jews instantaneously creating one community, singing, dancing and praying in one universal language – Hebrew. “

The history of Yellow Fever in the 19th century is fascinating. The disease, whose cause and cure was unknown at the time, was feared throughout the Americas. I have long been a student of the history of Yellow Fever since I lived in Norfolk, Virginia, which experienced its own calamitous outbreak in the 1800s. Anyone doing a casual reading of Buenos Aires history quickly learns that the 1871 was a critical event in the city’s history. It led the wealthy to flee San Telmo for the northern neighborhoods, giving cause to erect some of the city’s most incredible architecture in Barrio Norte. Learn more about the outbreak of 1871 Yellow Fever outbreak in Buenos Aires.

Next Page »

[Los Gauchos Judíos] by Alberto Gerchunoff. Through a series of 26 interlocking stories it conveys the history of Russian Jews who emigrated to Argentina. Set in Entre Rios province this small book creates a vivid picture of the life in the Jewish farm settlements. Gerchunoff’s own grandfather was one of the original Jewish colonists in Argentina. This book was first recommended to me by a Jewish colleague of mine in Miami who grew up in Rosario. She said that the stories in this book remind her of the stories that she heard as a young child in Argentina.

Julio Cortázar (1914-1984) is one of the towering figures of Argentine literature. Yet, Cortázar is hardly known in the English speaking world even among the very well educated. Generally, only the most literary of English language readers will be familiar with Cortázar. Archipelago Press in the U.S. recently released the first English translation of the Diary of Andrés Fava, translated by Anne McLean.

Julio Cortázar (1914-1984) is one of the towering figures of Argentine literature. Yet, Cortázar is hardly known in the English speaking world even among the very well educated. Generally, only the most literary of English language readers will be familiar with Cortázar. Archipelago Press in the U.S. recently released the first English translation of the Diary of Andrés Fava, translated by Anne McLean.