Not everyone reads the paper or watches the news on TV. But everyone sees the posters on the street.

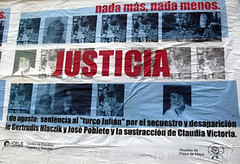

On Friday posters were pasted to the city’s walls proclaiming Justice against one of the most notorious torturers from the last dictatorship. The poster, sponsored by the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo and the Center for Legal and Social Studies, focuses on Julio Simón, known to his victims as Julián the Turk.

Simón was finally sentenced to 25 years in prison for his involvement in the kidnapping, torture, and forced disapperance in November 1978 of José Poblete, Gertrudis Hlaczik and their 8 month old daughter.

The long delay was caused by the Full Stop and Due Obedience Laws that provided impunity to those who participated in the military government that ruled Argentina from 1976 to 1983. Efforts to repeal the laws were finally successful in 2005.

Simón is the first person to be sentenced now that Full Stop and Due Obedience are no longer in effect.

“Legacies of Torture”

I first learned about the horrendous person that is Julio Simón, Julian the Turk, a few years ago when reading A Lexicon of Terror: Argentina and the Legacies of Torture

I first learned about the horrendous person that is Julio Simón, Julian the Turk, a few years ago when reading A Lexicon of Terror: Argentina and the Legacies of Torture  by Marguerite Feitlowitz. It’s an excellent book on the dark history of the last dictatorship and, along with Nunca Mas, should be required reading for anyone trying to understand contemporary Argentina.

by Marguerite Feitlowitz. It’s an excellent book on the dark history of the last dictatorship and, along with Nunca Mas, should be required reading for anyone trying to understand contemporary Argentina.

Described as a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Julián the Turk is said to love opera. One of his victims tells that Julián would bring tapes of classical music to the detention center and they would listen to it together. The same victim recounts horrors committed by Julián the Turk and the large swastika that hung on the end of a watch chain worn by Julián the Turk.

After the dictatorship ended some victims encountered Julián the Turk walking on the streets and were warmly greeted by their former torturer. Reading some accounts of the Dirty War and its aftermath can leave you with a bizarre feeling in which you wonder whether the old man sitting next to you on the bus is so kind.

On May 1, 1995 a taped interview with Julián the Turk was shown on the Buenos Aires news program Telenoche on Canal 13. One of his victims also was presented on the same program and said the following about Julián the Turk. Warning: graphic description of torture:

There was Julián standing over a prisoner they had naked, laid out on his belly, with his legs hanging down over the end of the table. Julián was torturing this man with an electric cable which he had shorn of its insulation and changed to 220 volts. It seems this wasn’t enough for Julián for he then inserted a stick into the man’s anus and then tortured him some more with the cable. As the man’s body writhed and jolted, the stick tore apart his intestines, and he died.

There’s also an odd story about competing news stations. Perhaps someone who was living here at the time might know more about it. Julián the Turk had pre-recorded his interview with Canal 13 but was irritated that he wasn’t going to be paid for his appearance. The station advertised heavily in the newspaper to promote the exclusive interview.

So, he went to the state-run TV station then called ATC (now Canal 7), which reportedly paid him for the interview and ATC aired the interview prior to his appearance on Canal 13.

On Canal 13 Julián the Turk appeared in a dirty turtleneck sweater and with a beard. On the ATC interview he was clean shaven with hair slick by gel and combed back. On ATC he told the interviewer, “What I did I did for my Fatherland, my faith, and my religion. Of course I would do it again.” (Feitlowitz 212).

The things nations do to fight terrorism

Marguerite Feitlowitz, who was conducting research for A Lexicon of Terror, met with Julián the Turk two months after the TV interviews at a café near where he was living in the Constitución section of Buenos Aires.

Julián the Turk immediately told her, “I am not repentant….This was a war to save the Nation from the terrorist hordes. Look, torture is eternal. It has always existed and always will. It is an essential part of the human being.” (Feitlowitz 212)

Feitlowitz writes:

Julián says the program on Channel 13 was “distorted. Not one innocent person passed through my hands.” He holds out his hands, which are large and muscular, with trunk-like fingers, and not entirely clean. What about the man with the stick in his bowels? He waves this away. The pregnant blind woman tortured and raped at his command? For some reason this gets to him, he denies ever having tortured “cripples.”

Justice – nothing more, nothing less

I know for a fact that there are a few educated porteños who believe that the actions of the government at that time were justified. Their arguments have the hauntingly, familiar tone that it was all about protecting the nation from terrorists. They say, “It was a war.”

It’s important to fight terrorism but it’s equally important for the state, for all countries, not to overstep human rights in that struggle. The path to justice and peace always seems decades away.

. That’s the American South not South America. But I think an interesting book to research and write someday is an examination and comparison of 19th century Yellow Fever epidemics in both North and South America. There are surely some fascinating stories to uncover. Well, guess I just add that to my long list of things to do!

I first learned about the horrendous person that is Julio Simón, Julian the Turk, a few years ago when reading

I first learned about the horrendous person that is Julio Simón, Julian the Turk, a few years ago when reading