Clarín, one of the leading daily papers in Buenos Aires, is issuing a special supplement over the next several Sundays titled La Fotografía en la Historia Argentina. The first volume came out today with over 125 photographs from the 1840s up to 1890. The next three volumes will cover the various decades up thru the return of democracy in the 1980s. The set should make for a nice pictorial overview of Argenine history.

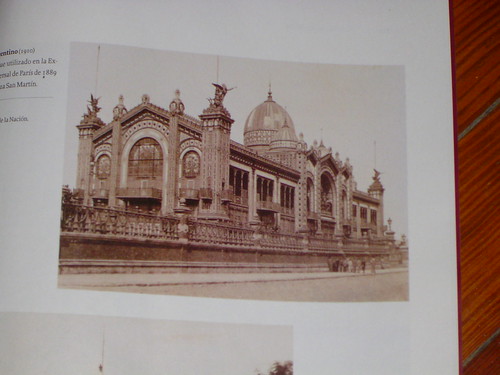

This week’s volume is useful for anyone studying the history of photography in Argentina, as it includes a reproduction of the first known daguerrotype that was made in Argentina. There’s a fascinating history behind 19th century photography and I’ll probably be writing about that at some point in the future. But now I want to focus on one particular photograph: the Argentine Pavilion at the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition.

One of my favorite spots in town is Plaza San Martín which sits at the end of busy calle Florida and Avenida Santa Fe, surrounded by some of the grandest buildings in Buenos Aires. Sloping down from the Plaza is a nice green space that leads to the Malvinas memorial and the English Tower. Plaza San Martín, with a huge equestrian statue of its namesake, is a nice, leafy spot where the nearby noise of the buses and traffic go almost unnoticed. Yet, the development of the Plaza, 70 years ago, involved the demolition of one of the architectural jewels of Buenos Aires.

The 1889 Paris Universal Exposition was one of the great world fairs and featured the completion of the Eiffel Tower. Argentina was about to enter what is sometimes called its “golden age”. Many of the magnificent buildings now lining the streets of Buenos Aires had yet to be constructed. The country eagerly wanted to adopt “globalization” at that time. National leaders saw the Paris Expo as an opportunity to present Argentina as a sophisticated partner for business, particularly agricultural trade.

The organizers of the Expo, however, viewed Argentina as just another undeveloped country and Argentina was asked to share a single pavilion with other Latin American countries. Argentina balked at this request and demanded a 6,000 square meter lot. They got 1,600 square meters instead. While its location next to the Eiffel Tower now seems an ideal spot, the adjoining areas were assigned to other Latin American countries and African colonies.

Argentina hired French architect Albert Ballu (1849-1939) and spent over 3.2 million francs on the construction of the pavilion. It was considered a masterpiece of iron and glass, 64 meters wide and 34 meters high. By all reports, the Argentine pavilion was a beautiful, highly ornated structure. The pavillion showcased the aspirations of Argentina, being built in the French style that would come to dominate Buenos Aires architecture over the next 40 years.

One scholar, in an excellent article on the pavilion, wrote “Argentina thus rewrote its identity fiction and defined itself as a European country, attractive to immigration….Argentina imagined itself closer to Europe than to Spain, which was erased from its national iconography. This desire to attract the attention of European investors threateningly suggested an interest in being recolonized, not by a ‘second-class’ metropolis – as Spain was then perceived – but by a first-class European colonial empire, such as France or Great Britain.” (Fernandez Bravo, Alvaro. “Ambivalent Argentina: Nationalism, Exoticism, and Latin Americanism at the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition”

Nepantla: Views from South – Volume 2, Issue 1, 2001, pp. 115-139)

Inside the pavilion were products that showcased Argentina’s trade goods. According to studies by Fernandez Bravo, the pavilion lacked any trace of culture. Refrigerated meat was one of the highlights.

After the Expo, the pavilion’s future was in doubt. While Ballu had built the pavilion with a flexible, screw-based architecture that could be disassembled for shipment back to Buenos Aires, the government of Argentina initially wanted to sale the building. The city of Buenos Aires eventually intervened and offered to pay half the shipping costs back to South America.

The iron in the pavilion weighed 890 tons. The furnishings and decorations added another 800 tons. Six thousand pieces were shipped back to Argentina. Some of the pieces were lost at sea due to rough waters.

In 1893 the pavilion was rebuilt on top of a ravine on calle Arenales between Maipú and Florida, what is now Plaza San Martín. The pavilion was useful and served as home of the Museo de Bellas Artes from 1910 until 1932.

In a case of serious short-sightedness the city decided to demolish the pavilion in order to create Plaza San Martin. While we can be thankful that it was replaced with a park and not one of those horrible modern skyscrapers that rose up in Buenos Aires during the 1930s, the loss of the pavilion is exemplary of problems with historic preservation in Buenos Aires – both past and present.

After the disassembly of the pavilion was completed in 1935, parts were sold for scrap iron. Other pieces of the pavilion were lost for more than sixty years. In the late 1990s a researcher discovered that some of the pavilion was being used as a shed for a blacksmith in Mataderos. Other pieces are still unknown but believed to have been buried alongside the railroad tracks in Palermo.

September 12th, 2005 at 8:49 pm

This kind of thing is right up my alley 🙂 It’s a great series of photos… I’ve got a lot of old pix & postcards that I use in my walking tours.

But if you’re really interested in the pavilion, you should get the book (or at least read it at El Ateneo!) “Plaza San Martín: imágenes de una historia.” It’s well-written & uses extensive archived photos. You’ll see that some of the pavilion is still on public view… you just have to know where to look 🙂 Two sculptures of “La Agricultura” are at Avenida San Isidro & Paroissien (Saavedra) + Avenida de la Riestra & Martín Leguizamón (Villa Lugano). “La Navegación” is at Avenida de los Incas & Zapiola (Colegiales). Finally, a big sculpture representing “La República Argentina” is at a school at Libertador & General Paz (Núñez). No one said finding them would be easy… but we have Carlos Thays to thank for that.

Don’t be too hard on Argentina for destroying the pavilion. That was the order of the day. They were meant to be temporary structures used only to show off wealth, technological advance, & the like… look at all the buildings from the Paris Expo that are no longer around… or the Crystal Palace in London. I agree that it’s a shame though. They would be nothing but breathtaking if seen today.