September 2005

Monthly Archive

Perhaps the characteristic that I enjoy most about Buenos Aires is its abundance of cafés. These are charming places where you can meet a friend or just sit leisurely reading, thinking, and writing. The United States has never been a “café society”, with the relatively recent exception of Starbucks (love it or hate it). Old-fashioned diners in the U.S. (and neighborhood bars, in some cities) often serve the same purpose as a gathering place but they certainly lack the intellecutal ambience of cafés in Buenos Aires.

While the Tortoni is ever popular among tourists I prefer the cafés that are not so fancy. When I walked further down Avenida de Mayo earlier this year and saw that they were remodeling 36 Billares, I was disappointed in the new decor. I remember being there a couple of years ago, sitting in the dim light by the open windows in the front, listening to the clinking sounds of the billiards tables and the shouts of the players. Maybe 36 Billares now is actually more like it was when it opened in 1894 but I prefer just to use my imagination for that. The cynic in me thinks that they are just trying to get a share of the tourist money. Indeed, as I walked by 36 Billares last week, they had tango dancers out on the sidewalk, urgh!

Last month La Nacion ran an article in its Sunday magazine about the places where Argentine writers choose to compose their works. Federico Andahazi, one of Argentina’s best contemporary novelists, describes his past fondness for writing in La Academia on Callao. There he started his first novel The Anatomist.

Regla general: trabajar en los bares. Requisito esencial: ocupar una mesa junto a la ventana. “No me molesta el ruido; ante la inexistencia del silencio perfecto, prefiero un bullicio sostenido. Me resulta imposible concentrarme en una biblioteca: el vuelo de una mosca se escucha como la turbina de un avión; el rechinar de una silla, como un movimiento tectónico, y un susurro, como el coro de una hinchada de fútbol”, dice.

Strangley, in New York City, a new enterprise called Paragraph has started. The business calls itself a “workspace for writers”. Paragraph leases out small desk space for writers at the rate of $100 (US dollars) a month. Or, $132 US if you want access to your desk between 6am and 6pm. Of course, leave it to my fellow US citizens to find a business opportunity that capitalizes on a non-existent need. If one wants quiet, then just go to a library. And are there that many writers whose apartments are so noisy at 3am that they must pay a hundred bucks a month for a place to go and think?! Yet, somehow, I suspect that Paragaph might take off and sprout up all over the country, just like Starbucks or Pottery Barn. (Paragraph‘s members only, application process, gives it a certain elitism that some might ascribe as “cool”.) The company’s web address, paragraphny.com, leads one to believe that they are already planning a paragraphdc, a paragraphla, etc…somehow, I just don’t expect that there will ever be a paragraphba.com. Argentine writers are much too smart for that. After all, Buenos Aires already has its own workspaces for writers in the cafés all over the city.

It’s well-known that Argentina has one of the highest literacy rates in Latin America. One admirable way that reading is encouraged is through low-cost editions published by the newspapers. Both of the main daily papers in Buenos Aires, Clarín & La Nacion, regularly re-release classic works by Argentine writers. Currently, La Nacion is honoring the close friendship between Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986)and Adolfo Bioy Casares (1914-1999) with a special edition of twenty books, a separate one every Wednesday. The price of each volume is only $4.90 with the purchase of La Nacion. That’s basically $1.70 US for a high quality piece of literature. What’s more remarkable about the price is that these same titles run about $35 pesos new in the bookstores. While Buenos Aires abounds with used bookstores I’ve seldom seen works by either of these writers in the second-hand shops.

When I came to Buenos Aires I knew that a major part of my time here would be spent reading Borges and Bioy Casares. So, I’m delighted to supplement my existing collection with these titles from La Nacion. The two writers are very different. While Borges now enjoys an immense international reputation, Bioy is probably a more enjoyable read for most people. While Bioy was not as experimental as Borges, Bioy is certainly a major 20th century writer though he is not particularly well-known outside of Argentina. Bioy wrote innovative narratives with intriguing, sometimes fantastical plots, in a clean and crisp prose. Bioy also is fortunate to have a very good English translator in the form of Suzanne Jill Irvine.

In other postings I’m going to discuss each of the works by Borges and Bioy being re-issued by La Nacion. First, though, I want to talk some about their friendship.

Bioy, who came from a very wealthy family, was 18 when he first met the 32 year old Borges. At that time Borges still was a struggling writer, decades from the international fame that he would later achieve. Their friendship would develop over a number of years and last through the rest of their lives, often resulting in collaborative works.

Another person who figures prominently in this friendship is Bioy’s wife Silvina Ocampo, sister of the Argentine cultural matriach Victoria Ocampo. A writer of haunting stories about childhood, Silvinia Ocampo is one of the most underrated writers to come out of mid-twentieth century Argentina. She always was in the shadow of her husband and Borges. Unfortunately, very little of her works have been translated into English.

For many years Borges would spend almost every evening with the Bioys. First at their Recoleta apartment on Ave Santa Fe and then later when the Bioys moved to a larger, more posh apartment on Posadas. On Thursday nights the Bioys often would invite a few guests over to dinner. One of Borges’ biographers described the Bioy’s home as a “congenial haven for Borges at a time when he was acutely unhappy.”

Look for more on Bioy and Borges in the coming weeks.

On the first of this month we finally made our move to San Telmo on a Wednesday night. We are now living in this lovely old building (thanks to our friend Adriana!). Our apartment is the top floor, front, with wonderful windows that open out onto to calle Brasil. It’s an old place that needed a lot of restoration. No one had lived in the apartment had been abandoned for 10 years and, from the looks of it, nothing had been done to apartment for the previous thirty years. Adriana and Ceci spent a lot of time working on it. This photo of the living room is rather dark but it nicely shows the window over the door. Later, I’ll post a picture of the building itself.

One interesting aspect of the building is the staircase. The entrance opens into a small covered hallway, which in turns leads to a long open-air corridor. A spiral staircase winds it way up to the top floor where we live. There’s no elevator so we get plenty of exercise going up and down the stairs. But it’s a lovely staircase, particularly at night when the light cast shadows of the ironwork onto the steps.

Clarín, one of the leading daily papers in Buenos Aires, is issuing a special supplement over the next several Sundays titled La Fotografía en la Historia Argentina. The first volume came out today with over 125 photographs from the 1840s up to 1890. The next three volumes will cover the various decades up thru the return of democracy in the 1980s. The set should make for a nice pictorial overview of Argenine history.

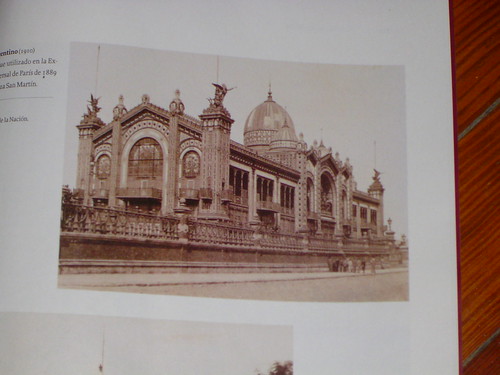

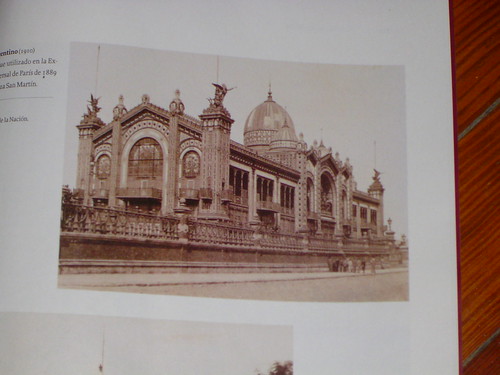

This week’s volume is useful for anyone studying the history of photography in Argentina, as it includes a reproduction of the first known daguerrotype that was made in Argentina. There’s a fascinating history behind 19th century photography and I’ll probably be writing about that at some point in the future. But now I want to focus on one particular photograph: the Argentine Pavilion at the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition.

One of my favorite spots in town is Plaza San Martín which sits at the end of busy calle Florida and Avenida Santa Fe, surrounded by some of the grandest buildings in Buenos Aires. Sloping down from the Plaza is a nice green space that leads to the Malvinas memorial and the English Tower. Plaza San Martín, with a huge equestrian statue of its namesake, is a nice, leafy spot where the nearby noise of the buses and traffic go almost unnoticed. Yet, the development of the Plaza, 70 years ago, involved the demolition of one of the architectural jewels of Buenos Aires.

The 1889 Paris Universal Exposition was one of the great world fairs and featured the completion of the Eiffel Tower. Argentina was about to enter what is sometimes called its “golden age”. Many of the magnificent buildings now lining the streets of Buenos Aires had yet to be constructed. The country eagerly wanted to adopt “globalization” at that time. National leaders saw the Paris Expo as an opportunity to present Argentina as a sophisticated partner for business, particularly agricultural trade.

The organizers of the Expo, however, viewed Argentina as just another undeveloped country and Argentina was asked to share a single pavilion with other Latin American countries. Argentina balked at this request and demanded a 6,000 square meter lot. They got 1,600 square meters instead. While its location next to the Eiffel Tower now seems an ideal spot, the adjoining areas were assigned to other Latin American countries and African colonies.

Argentina hired French architect Albert Ballu (1849-1939) and spent over 3.2 million francs on the construction of the pavilion. It was considered a masterpiece of iron and glass, 64 meters wide and 34 meters high. By all reports, the Argentine pavilion was a beautiful, highly ornated structure. The pavillion showcased the aspirations of Argentina, being built in the French style that would come to dominate Buenos Aires architecture over the next 40 years.

One scholar, in an excellent article on the pavilion, wrote “Argentina thus rewrote its identity fiction and defined itself as a European country, attractive to immigration….Argentina imagined itself closer to Europe than to Spain, which was erased from its national iconography. This desire to attract the attention of European investors threateningly suggested an interest in being recolonized, not by a ‘second-class’ metropolis – as Spain was then perceived – but by a first-class European colonial empire, such as France or Great Britain.” (Fernandez Bravo, Alvaro. “Ambivalent Argentina: Nationalism, Exoticism, and Latin Americanism at the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition”

Nepantla: Views from South – Volume 2, Issue 1, 2001, pp. 115-139)

Inside the pavilion were products that showcased Argentina’s trade goods. According to studies by Fernandez Bravo, the pavilion lacked any trace of culture. Refrigerated meat was one of the highlights.

After the Expo, the pavilion’s future was in doubt. While Ballu had built the pavilion with a flexible, screw-based architecture that could be disassembled for shipment back to Buenos Aires, the government of Argentina initially wanted to sale the building. The city of Buenos Aires eventually intervened and offered to pay half the shipping costs back to South America.

The iron in the pavilion weighed 890 tons. The furnishings and decorations added another 800 tons. Six thousand pieces were shipped back to Argentina. Some of the pieces were lost at sea due to rough waters.

In 1893 the pavilion was rebuilt on top of a ravine on calle Arenales between Maipú and Florida, what is now Plaza San Martín. The pavilion was useful and served as home of the Museo de Bellas Artes from 1910 until 1932.

In a case of serious short-sightedness the city decided to demolish the pavilion in order to create Plaza San Martin. While we can be thankful that it was replaced with a park and not one of those horrible modern skyscrapers that rose up in Buenos Aires during the 1930s, the loss of the pavilion is exemplary of problems with historic preservation in Buenos Aires – both past and present.

After the disassembly of the pavilion was completed in 1935, parts were sold for scrap iron. Other pieces of the pavilion were lost for more than sixty years. In the late 1990s a researcher discovered that some of the pavilion was being used as a shed for a blacksmith in Mataderos. Other pieces are still unknown but believed to have been buried alongside the railroad tracks in Palermo.

This posting continues Piqueteros, the Argentine Government, & the Right to March into Plaza de Mayo.

What should have been an anti-Bush rally in Plaza de Mayo turned into a stubborn, violent standoff between police and piqueteros about the right to march down Avenida de Mayo and into Plaza de Mayo.

The march was scheduled to commence at 5pm from Congreso. I was running late and didn’t leave our apartment in San Telmo until a quarter till five. Thinking that the subway would be quick, I walked over to Constitucion station to find that it was packed with piqueteros on their way to the march. Then I realized that the march was on “Argentina time” and probably would start at least an hour late.

I got off the subte at the Av de Mayo stop on the “C” line to find that the exits from the subway to the street were locked. (Ok, Argentina, didn’t you learn anything about fire safety and locked exits from Cromagnon?! Alright, maybe that’s a little harsh but there’s an appalling lack of fire safety awareness in this city…yet another post). Anyway, there were several of us who had gotten off the subte and wanted to exit onto Av de Mayo. At first the official at the station just shrugged his shoulders and suggested that we get back on the subte and get off at another stop. One man in a business suit said to him, “We’re not piqueteros.” Soon, the official led us up the steps and unlocked the gate.

As I walked down Av de Mayo towards the Congreso, I noticed a large number of people walking in the same direction. The Avenue was closed and a few of the people were piqueteros going to join up with the rest of the marchers who were gathering in front the Congreso. But, most were simply ordinary people getting off from work on a Friday afternoon during rush hour only to find that the “A” subway line which runs underneath Av de Mayo was closed due to the protest. None of these people looked too happy. I have to say that I didn’t see any reason for the city to close the subway line, though I’m sure that the city said that they had to do that for safety reasons.

Once I got to Congreso I could tell by everyone sitting around that the march was at least a good hour away from starting. So, I wandered back down Av de Mayo towards the Plaza. As my previous post discussed, there had been significant controversy over the right of protesters to enter Plaza de Mayo and I was pleased to hear that the marchers were going to be allowed to enter freely.

Yet, as I crossed Av 9 de Julio, I saw a massive police presence gathered at the intersection of Av de Mayo and 9 de Julio. Walking around the police, I saw the riot squads lined up against the wall of a cafe and waiting. Parked half-a-block away was an armored police vehicle with two water cannons mounted on top. I stopped to look at that vehicle, glanced around, and realized that the police again had no intention of letting the marchers proceed to the Plaza.

So, I waited around to see what was going to happen. As the marchers got nearer, the police formed a double line of officers that closed off Av de Mayo. A swarm of photographers and news media started gathering in front of the officers to wait for the marchers. Standing next to me was a TV reporter interviewing a senior police official about whether the marchers would be allowed to enter Plaza de Mayo. The official said, “Yes, they can enter Plaza de Mayo but they cannot march down Av de Mayo. They will need to go down Av 9 de Julio, down Av Belgrano, and enter the Plaza from Av Roca.” The reporter asked again, if the marchers could enter the Plaza and the officer re-confirmed that they could if they took this route.

From the point where the police blocked Av de Mayo, it is only 5 blocks to the Plaza. On the new route ordered by the police, the marchers would have to go an extra 4 blocks, for a total of 9 blocks. Not really a long way, but clearly not the most direct path. I heard that an offical reason for this new route was to prevent traffic problems. What?! The new route obviously would cause more traffic jams than just letting the marchers walk down Av de Mayo.

The police roadblock of Av de Mayo seemed clearly to be a message from the Kirchner government to the piqueteros about who was in charge: the government. There was an incredible display of police force present. Indeed, I would say that the police presence was excessive, much more than I had seen at any other march this year. Of course, the police (I’m sure acting on orders of the government) were clearly intending to be confrontational.

If the march would have been allowed to continue, then it likely would have been peaceful. However, the tension escalated into a couple of pushing matches between police and a few protesters. I lost track of time during all this, but it must have been more than an hour, or an hour and a half, that this standoff continued. Reportedly, eleven police officers were injured tonight. For most of the time, I was standing right next to the police line and I’m not sure how that happened. I suspect that several of the injured officers were hurt by their riot police as the riot squad with their clubs swinging came jumping over the regular police. I did see one photographer who ended up with a bloody face.

The police intensified their presence by bringing a second armored vehicle with water cannons pointing towards the protesters. I took a few minutes to walk around to get a sense of the crowd. The protesters towards the front of the march were, actually, mostly students. When I realized this, I became even more dismayed at the police force. So, I started taking photographs of the students in the march. In the event that the police used water cannons on these students, who were obviously being well-behaved, I wanted to document who that they were peaceful. These students, late teens/early twenties, were there to protest George Bush’s visit to Argentina in November and were not part of the piquetero movement. It would have been a shame if these students had gotten injured by the police.

I do not want to fault the police and the government entirely for tonight’s conflict. The piqueteros share some of the blame. Rather than accepting the police invitation to a confrontation, the marchers easily could have gone along the suggested route of Av 9 de Julio, Belgrano, and Av Roca to Plaza de Mayo. Indeed, it would have resulted in a bigger protest by blocking even more streets and causing more traffic problems. In this scenario, the police would have ended up looking silly for creating even further gridlock than was necessary. Yet, the marchers who appeared to be under the leadership of the piqueteros did not do that. They held their ground in the middle of 9 de Julio. In my opinion, that was a significant miscalculation since the issue was not the right to march down Av de Mayo but instead the right to enter Plaza de Mayo.

Well, actually, the focus of the march was supposed to be anti-Bush but that somehow got lost in the tense standoff. Dubya should thank Kirchner for that. I never suspected that Kirchner, who has hosted Chavez and Castro, was so supportive of the Bush administration. The people of Argentina had a chance to send a message to Washington tonight but they let internal politics get in the way. There was some sarcasm on my part in this paragraph. But, I do think that a lot of people in the march knew that tonight’s protest wasn’t about Bush but was more about piquetero-government relations.

As I was standing around watching this all unfold tonight, I had a chance to think about the piqueteros. I’ve never really been bothered by their roadblocks, but maybe that’s because I don’t drive here. Also, I think that people who are clearly impoverished and on the margins of society have a right to protest and to exercise their political voice.

I am disturbed, however, by the potential for violence on the part of the piqueteros. Why do they need to carry those big sticks unless they plan to engage in violence? As I walked around the crowd of student protesters, I also observed several piqueteros who were arming themselves for a violent encounter with the police. One piquetero was standing behind a group of students. Clinched in his hands was a slingshot, made of thick rubber. He was ready to fight. But, he was no schoolyard bully; he was a grown man in his thirties. On the other side of more students were piqueteros breaking apart the sidewalk, taking chunks of concrete. They were ready to fight the police.

As the marchers gave up and moved away towards the Obelisc, a couple of piqueteros hung back and flung stones at the police. Indeed, it was remarkable restraint on the part of the police not to pursue and arrest the them. But, the police, with their riot gear and water cannons let the stone throwers walk off into the night.

As the marchers gave up and moved away towards the Obelisc, a couple of piqueteros hung back and flung stones at the police. Indeed, it was remarkable restraint on the part of the police not to pursue and arrest the them. But, the police, with their riot gear and water cannons let the stone throwers walk off into the night.

Kirchner has called for the piqueteros to stop blocking the streets before the government will sit down and negotiate with them. I have less of a problem with piqueteros blocking the streets, but they need to lay down their sticks and stones. Peaceful, non-violent protests have proven to be remarkably successful as a way of galvanizing international attention on social problems and injustices. There’s a perfectly good example here in Argentina with the Madres de Plaza de Mayo.

Up until now the piquetero marches that I’ve seen have been remarkably peaceful. In looking at the crowds of piqueteros it’s obvious that they are mostly good people. Yet, among them, are an angry violent few that are ruining the reputation of the entire movement.

The piquetero leadership needs to re-examine its tactics. Likewise, the Kirchner government shouldn’t act so stubborn and create unnecessary conflicts that lead to violence.

Plaza de Mayo always has been a popular gathering spot for political assemblies in Buenos Aires. It’s the historic plaza of the city: on one end of the Plaza is the 18th century cabildo and the city goverment building, on the other side of the Plaza is Casa Rosada, which houses the executive branch of the Argentine government. Leading away from the plaza is Avenida de Mayo, one of the grandest avenues in the city, stretching for thirteen blocks, culminating in the Congreso.

One controversy this week has been the recent decree by Aníbal Fernández, Minister of the Interior, that marchers will need permits to march into Plaza de Mayo. This new regulation came after piqueteros camped out for a week in the Plaza and when marchers were blocked by police last Friday. There was a significant outcry in the city about this new restriction. A lawsuit was filed in the courts stating that such actions have not been seen since the end of the dictatorship. One of the founders of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo, the most well-known human rights group in Argentina, stated that the Plaza needs to remain a symbol of freedom for the country. Yet, the restriction was primarily directed against the piquetero movement, a loose confederation of political and social groups comprised of the unemployed and the working class. The piqueteros most common form of political expression are marches and roadblocks, which snarl the already congested traffic in the capital city.

I normally agree with the government of Nestor Kirchner, President of Argentina. However, I was concerned that this new restriction was mostly a political tool. Congressional elections in Argentina are to be held next month and Kirchner has come down hard on the piqueteros recently as a way to appease the middle-class, which is often frustrated by the traffic jams caused by the piquetero roadblocks. (Next month’s elections deserve their own series of postings, particularly the almost absurd senatorial campaign between Kirchner’s wife Christina and previous Argentine President Duhalde´s wife Chiche).

So, it seems like Plaza de Mayo briefly became a political hostage. Earlier this week I saw a small group of protestors (artisans and hippies, not piqueteros) turned away from the Plaza, stopped by the police just a block away at the intersection of calle Florida and Av de Mayo. However, towards the end of the week, Interior Minister Fernandez announced that this evening’s marchers would be allowed to enter Plaza de Mayo. Yet, it turned out that there was a little surprised waiting for them. See my next posting about the march.

« Previous Page